Liquidation Preference Explained: What Founders and Investors Need to Know

When startups raise money from investors, the term “liquidation preference” often appears in term sheets and conversations. At first glance, it might sound like just another piece of legal jargon, but in reality, it can have a huge impact on who gets paid—and how much—if the company gets sold, acquired, or even shuts down.

In fact, a 2023 analysis by PitchBook showed that over 95% of venture capital deals included some form of liquidation preference. For founders, this means understanding liquidation preference isn’t just nice to have—it’s essential if you want to know what could happen at your startup’s exit. And for investors, it’s often a primary tool to protect their investment and set expectations from day one.

In this article, we’ll break down what liquidation preference actually means, why it exists, and how it works. You’ll see real-world examples, understand the difference between participating and non-participating terms, and learn why founders and investors sometimes end up on different sides of the table when this clause is discussed.

Defining Liquidation Preference

Liquidation preference is a crucial feature in venture capital deals, determining how proceeds are distributed when a company is sold, merged, or shut down. At its core, it answers the question: who gets paid first, and how much, when money is on the table?

Why Liquidation Preference Exists

When investors take the risk of backing a young company, they want some assurance that they’ll recover their investment if things go sideways. Liquidation preference is that safety net. It’s designed to protect investors from losing out entirely if a startup exits for less than everyone hoped. It spells out precisely what portion of the sale, liquidation, or merger proceeds investors are entitled to recoup before anyone else receives anything.

When Liquidation Preferences Apply

Liquidation preferences aren’t just triggered by the company going out of business. They also come into play during acquisitions and mergers—essentially, any situation where the company’s assets are being sold or transferred. Investors with a liquidation preference are first in line to get their share according to exact terms spelled out in the investment agreement. If the pie is small, these terms matter even more, especially for founders and employees whose shares might end up worth less than expected.

Understanding this concept sets the stage for exploring how liquidation preferences are actually implemented—and why their details can dramatically affect the fate of a startup’s stakeholders.

How Liquidation Preferences Actually Work

Basic Mechanics: Who Gets Paid and When

Liquidation preference kicks in the moment there’s an exit that produces cash for shareholders—think acquisition, merger, or winding down. Instead of simply splitting the payout by ownership percentages, investors with liquidation preferences are first in line to get their money back, up to a specific amount. Only after these claims are satisfied does any leftover cash flow to the other shareholders, usually founders and employees holding common stock.

1x, 2x, and Beyond: Multiples and What They Mean

Multiples represent how much money investors get before anyone else sees a dime. A “1x” liquidation preference means preferred shareholders get back what they invested, dollar for dollar, before common shareholders receive anything. A “2x” preference doubles their initial investment, and so on. In tough exits, this can leave little or nothing for everyone else if the multiples and deal size don’t add up favorably.

Liquidation Waterfall: Priority and Stacking

When a company has raised several rounds of investment, each with its own liquidation preference, payments follow a sequence called a “liquidation waterfall.” The most senior preferred shares—usually the last investors in—get paid first, followed by earlier investors, all before common shareholders. This stacking means payout calculations can become complex quickly.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/term-out-v1-6ef5969de7d44f189ab6170a0c037306.png)

The waterfall visually explains how money flows: top to bottom, preference by preference, until there’s nothing left to distribute. This is why founders and early employees can walk away empty-handed even if the company sells for millions—it all depends on the details and amount of liquidation preferences stacked up over time.

Now that you understand how preference works layer by layer, let’s explore the flavors these preferences come in—and why not all preferences are created equal.

Types of Liquidation Preference

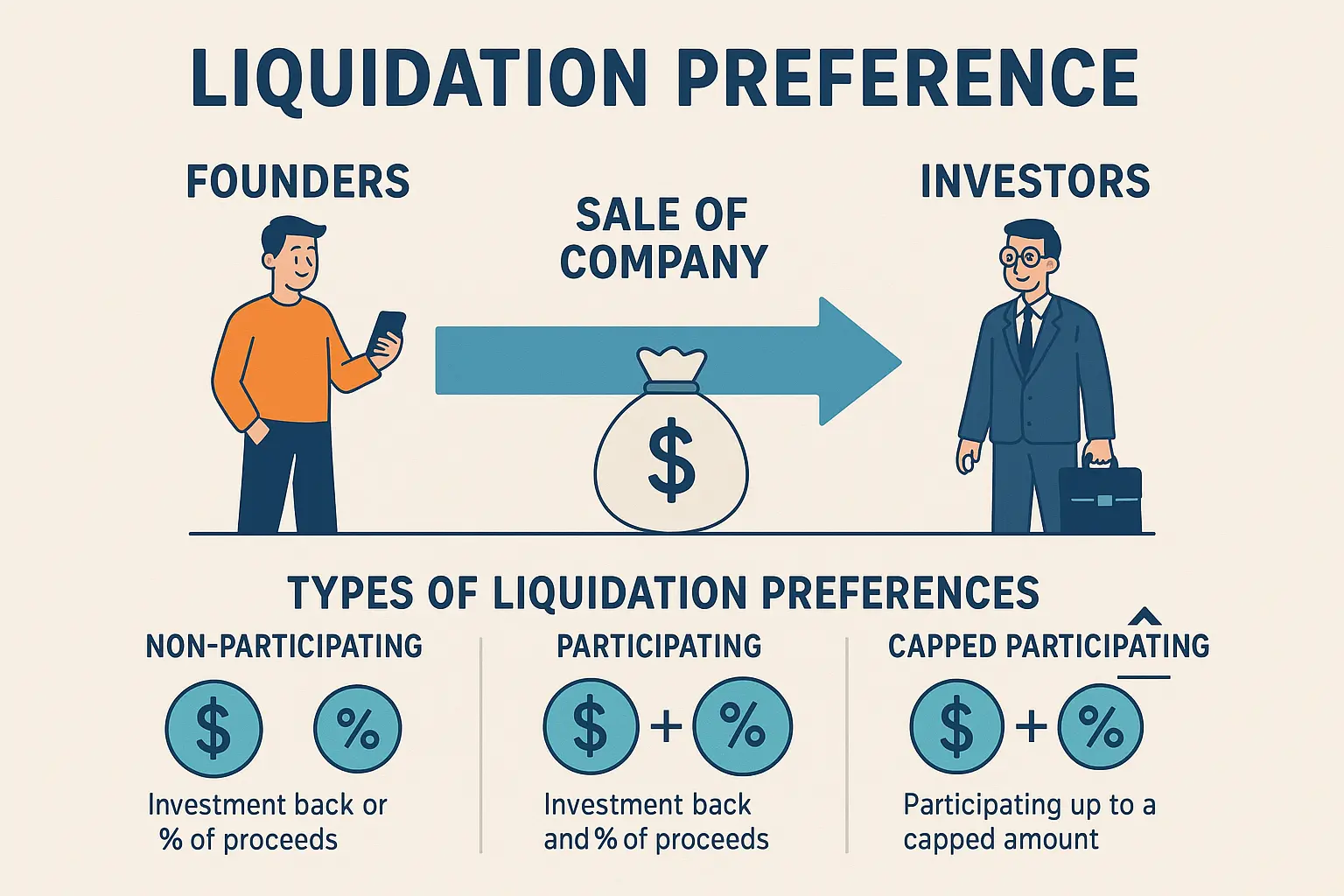

Non-Participating vs. Participating

Liquidation preference can be split into two main styles: non-participating and participating. With a non-participating preference, the investor chooses between getting their original investment back (sometimes with a multiple) or converting their preferred shares to common and taking part in the split with everyone else. It’s “either-or”—not both.

Participating preference, on the other hand, lets the investor “double dip.” First, they get their initial investment back. Then, they also join in splitting the rest of what’s left with common shareholders. This means participating preference often lets investors walk away with much more money, especially in smaller exits.

Capped Participation

Sometimes, participating preferences come with a cap to keep things from getting excessive. The cap sets a maximum return—often stated as a multiple of the original investment—after which the investor’s participation stops. Capped participation aims to strike a balance: investors get upside, but it isn’t unlimited, so founders and employees can still see real returns if there’s a good outcome.

Knowing exactly which type of liquidation preference is in play is critical—it has a real impact on who gets what in any kind of sale or exit. Next, let’s see how these different preferences actually shape real-world outcomes, both for investors and startup teams.

Liquidation Preference in Real Scenarios

Example Calculations for Startups

Imagine a startup that raised $2 million from investors under a 2x non-participating liquidation preference. The company later sells for $5 million. The investors are entitled to receive twice their original investment before any money goes to common shareholders. In this case, the investors receive $4 million (2 x $2M). The remaining $1 million is split among the founders and team with common stock. There are no further proceeds for the investors after their preference is satisfied.

Now, consider the same scenario, but with a participating liquidation preference. The investors would first collect $4 million (2 x $2M), then also share in the remaining $1 million alongside the founders, according to their equity percentage. This double-dip can dramatically reduce the amount founders receive from an exit, especially at modest acquisition prices.

Impact on Common Shareholders and Founders

Liquidation preferences directly affect what founders and employees take home. If sale proceeds barely cover the investors’ preference, common shareholders could see little or nothing, even if a company sells for more than its total investment. As a result, preferred terms like 2x or full participation can drain founder motivation and skew incentives, making it critical to understand exactly how these structures play out at different exit values.

Knowing these real outcomes can turn vague term sheet language into concrete dollar amounts. By breaking down the numbers on paper, founders and early employees gain clarity—and leverage—when discussing what’s truly at stake.

Of course, understanding the numbers is just one part. Next, we’ll cover how to spot the specific terms that shape these outcomes and what to watch for when reviewing offers.

Ready to Take Your Understanding Further?

Liquidation preference isn’t just a technicality—it’s a pivotal part of every fundraising conversation, shaping both your upside and your downside. Whether you’re mapping out your first term sheet or looking to revisit a previous deal, a strong grip on these basics can prevent slip-ups that cost you equity—or payouts—later.

Still have questions about how a specific preference might play out for your company or deal? Don’t make assumptions. Make thoughtful decisions. Reach out to us, or dig deeper with our guides and tools tailored for founders and investors navigating these key moments.

Curious about what actually makes it onto the page when you’re negotiating? Let’s break down the exact terms that show up in a term sheet next, so you know exactly what to look for and how to spot favorable (or risky) wording before you sign.

Thank you for reading EasyVC’s blog!

Are you looking for investors for your startup?

Try EasyVC for free and automate your investor outreach through portfolio founders!

Negotiating Liquidation Preferences in Term Sheets

Key Terms to Watch Out For

When a term sheet lands on the table, a close look at liquidation preference clauses is essential. Terms such as the preference multiple (like 1x or 2x), participation rights (“participating” vs. “non-participating”), and any caps or thresholds directly shape exit outcomes. A seemingly minor word—like “participating”—can mean the difference between a fair share and a disproportionately large payout to investors. Make sure you understand whether preferences include accrued dividends, if there’s a cap on participation, and how preferences “stack” if multiple rounds are involved. Even the timing—such as who gets paid first and how any remaining funds are distributed—matters more than many realize in less-than-blockbuster exits.

Balancing Investor Protection and Founder Incentives

Investors use liquidation preferences to safeguard their cash, but these same protections can diminish the returns to founders and employees, creating lopsided incentives. The best term sheets try to reconcile both sides: giving investors reasonable downside protection without stripping founders of motivation. It’s rarely just about the headline number—sometimes a lower multiple or capped participation, coupled with reasonable triggers for conversion, ensures alignment. Open negotiation about what’s fair in light of the company’s stage, market, and risk profile helps both sides land on terms that support company growth while keeping everyone committed for the long haul.

Once the liquidation preference language is squared away, attention should turn to other clauses that affect outcomes in scenarios founders and investors rarely imagine—yet too often regret not considering.

Frequently Asked Questions About Liquidation Preference

Does Liquidation Preference Apply in All Exit Events?

No, not every exit triggers liquidation preferences. They typically come into play during “liquidation events” such as acquisitions, mergers, or asset sales—any scenario where the company is being sold or shut down and proceeds are distributed. In contrast, IPOs or stock sales on secondary markets often convert preferred shares to common stock, sometimes negating the preference. Always review the specific terms in the investment agreement—details matter.

Can Preferences Be Changed or Waived?

Yes, preferences aren’t set in stone. Investors and founders can renegotiate or entirely waive liquidation preferences, especially during future fundraising rounds. Occasionally, these negotiations happen if current terms block important deals or harm alignment between investors and the founding team. However, waiving usually requires approval from the affected shareholders or the board, so consensus is essential.

Understanding how these terms play out in real scenarios is crucial for both founders and investors—let’s look next at how liquidation preference impacts actual startup outcomes.

Final Thoughts: Getting Liquidation Preference Right

Liquidation preference isn’t just a footnote in your term sheet; it holds real power over who receives what in the event of a sale. When founders and investors take the time to dig into the details, both parties can align interests while protecting against surprises down the road. It’s not about trying to squeeze every possible advantage out of the deal; it’s about designing fair terms that reward risk and effort in the right balance.

Remember, there’s no perfect “industry standard” here. Each deal reflects a unique set of business realities, investor appetites, and founder goals. A single extra clause or percentage point can tilt the stakes, so clarity and communication are crucial throughout negotiations. When liquidation preference is transparent and well-understood, it gives everyone a clearer picture of the future—no matter what the exit holds.

With this foundation in place, it’s time to drill into the specific techniques and terms you’ll encounter when these provisions land on your desk for negotiation.